Set problems for players to solve.

Think of skilled behavior when you see it in a soccer game. There is obviously an inherent adaptiveness built into what we observe. Imagine if a player passed or dribbled exactly the way they do in those lines we put them through at practice. Of course, they wouldn’t want to behave this way in a game, that is obvious.

However, it is apparent that the training in which many of us coaches in youth sport are convinced is building the foundation for skilled behavior is, in fact, doing so. But the foundation is actually very brittle when it tries to adapt to the winds from the storm of the game.

Think of the process of how we plant trees in the environment and how we provide them with the necessary extra care in terms of mulching, watering, and a response-ability to pay attention to the elements the tree is enduring in its early stages. In this process, we never remove it from the environment in which the tree is forming within to inhabit.

The same is true for player learning in development. (Notice the “in” between the two). This distinction, which I believe was first described by Adolph in “An ecological approach to learning in (not and) development.” (2019) does a fantastic job of highlighting important differences between these two interconnected concepts.

The difference makes sense. Development is an ongoing process of growth and maturation over the course of a life, and learning is the adaptation process that occurs amidst these developmental changes. In other words, a child has no choice but to develop, and they are learning to adapt within the complexity of the game amidst that development.

Just as the tree could be overwhelmed in a harsh climate in its early stages without proper care, I believe the same is true for a developing youth.

In their recent paper, Uehara and colleagues examined the influence of families and football academies on the pathway to football expertise of Brazilian Players (2022). In it, they make the beautiful recommendation “To enhance the probability of developing successful football players, both families and academies must work synergistically with communication and understanding so that the players in development can feel secure and confident to pursue their dreams.” (Uehara et. al 2022).

Also, as referenced in the same paper, the above recommendation is also in line with another recent study by Teques and colleagues that found that perceptions of elite youth athletes were that of parental practices that were based in reinforcement, encouragement, and role modeling all had significant effects on athlete intrinsic motivation in comparison to sub-elite peers.

Of course, more research needs to be done, but I find it pretty intuitive that youth who receive love and support at early ages enhance their ability to adapt to the complex environment they are trying to inhabit. Read that paper to also consider the distinction between financial support, and emotional support. Which do you think children receive more of in America?

This begs the question, which environment are the players learning to adapt in. They are developing nonetheless, but where they are learning within that developmental journey is important to consider.

Are the players learning to explore how to adapt in environments that will help them be stable in the complexity of the game? Or are they learning to explore how to adapt in environments that create a brittle foundation that has them falling over from the gusts of wind? More often than not, I observe the latter.

(EDIT) In traditional drills the focus is on repeating a solution until it becomes “automatic”. What is actually happening is that the players are becoming “static” in the context on the game. Skill is a functional, adaptive, individual-environment relationship. Varied repetition of problem solving, not repetitious drills that do not vary. (Referencing Nikolai Bernstein’s notion of repetition without repetition – learn more here). Or as my good friend says, “Skill is repeating the process of finding a solution”. Hence the importance of problem solving.

These questions are exactly what many researchers, practitioners, doctors, psychologists etc are exploring in the massive and ever-growing field of Ecological Dynamics.

Mark O’Sullivan, James Vaughan, Carl Woods, and Keith Davids do a great job in creating a framework for applying an ecological dynamics rationale in any sporting environment in their paper, “Towards a Contemporary Player Learning and Development Framework for Sports Practitioners” (2021). I highly recommend checking it out if you are a coach in any field.

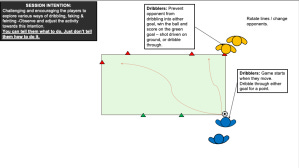

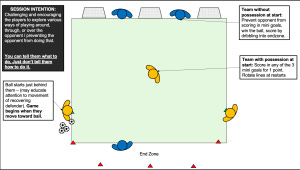

Setting problems for players to solve is a great way to start encouraging them to be adaptive. Two activities, such as a 1v1 and a 3v3, are good examples. (See below)

Designing sessions requires a lot of thought. One way to do it well is to focus on setting problems for the players to solve. You can tell them what to do, but not how to do it. By leaving gaps in your instructions, you create room for players to learn to creatively achieve the objectives. This is what being ecological is all about: designing representative environments that promote exploration of how to solve problems.

Think of exploration within environments that include specifying information as the precursor for learning, whether it is for athletes or coaches themselves.

Good sessions should include the necessary “information sources” that can aid in a player’s becoming more adaptive in game contexts. These sources are: a ball, opponent(s)/teammates, direction, consequence, scoring, boundaries, and representative information.

Representative information is information that is representative of what the player would need to pay attention to in the game. For example, in the 3v3 example below, promoting unrepresentative information – “Must complete 3 passes before you can score” – may get the players to look for passes, but it would shape their intentions and guide their attention away from what would be important in a game without that rule.

The important information is available, for free (as Rob Gray would say), in representative environments. As coaches, our job is in part to shape the players’ intentions and guide their attention towards the information that is available for them to discover as useful.

References

Adolph KE. An ecological approach to learning in (not and) development. Hum Dev 2019; 63: 180–201.

Uehara, L., Davids, K., Pepping, G.-J., Gray, R., & Button, C. (2022). The role of family and football academy in developing Brazilian football expertise. International Sports Studies, 44(2), 6–21. doi:10.30819/iss.44-2.02

Sullivan, M. O., Woods, C. T., Vaughan, J., & Davids, K. (2021). Towards a contemporary player learning in development framework for sports practitioners. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 16(5), 1214–1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541211002335